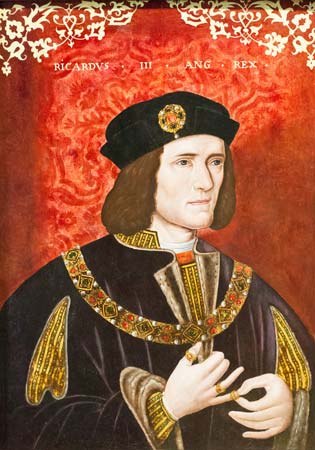

The mystery surrounding the fate and probable murder of the Princes in the Tower has preoccupied historians for over 500 years. Rumours that they had been put to death on the orders of their uncle, the newly anointed Richard III, destabilised his reign and ultimately contributed to his brutal end on Bosworth Field.

This is not the place to re-run those arguments. I have blogged about them separately.

Today, we look at a different question. When Richard allowed the boys to be declared illegitimate and took the throne for himself, was he acting out of ruthless self-interest? Or did he have genuine grounds to believe that his nephews were not the lawfully begotten children of his brother, Edward IV?

According to supporters of Richard III, Edward V and his brother, Richard, Duke of York were illegitimate. Their parents had never been lawfully married. Before marrying their mother, Elizabeth Wydeville, Edward IV had pre-contracted himself (a kind of informal, but legally binding, marriage) to Lady Eleanor Talbot, daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury.

This question is separate from the debate around whether Richard had his nephews put to death. It is quite possible to believe that he seized the throne illegally, but never took it upon himself to eliminate the Princes. Some historians, conversely, believe that he was within his rights to declare himself King, but still decided to eliminate rival blood.

Nevertheless, our understanding of this question frames the tone for the rest of the debate. Those that view him as a reluctant King, dragged to power for the good of the nation are less likely to deem him capable of child murder. Historians that judge he usurped the right of the nephews he should have protected, are more prepared to recognise his ruthless streak.

But this question must be looked at in isolation. Each of the arguments should be assessed on their own merits. Doing so, has led me to a clear conclusion: that there is every reason to believe the pre-contract story is a complete invention. Here’s just four of them.

1.The convenience of the timing

The story emerged at a very convenient time. Why had no one mentioned it in 1464 when Edward and Elizabeth married? It is understandable that no one would have challenged Edward at the height of his power. But at the time of his controversial marriage there were many people – who were effectively just as powerful as him – who were shocked and appalled. They would have paid handsomely for any information to nullify the Wydeville marriage. The fact that none came forward suggests none existed.

2. Richard and his supporters tried other ways of discrediting the Princes first

It is clear from the contemporary writings of Dominic Mancini that this was not even Richard’s plan A. He and his supporters first put it about that Edward IV himself was illegitimate – the result of their mother’s adultery. They also argued that Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville had been invalid because of its secretive and lustful beginnings. It was a case of throwing around a few stories and seeing what stuck.

3. If Richard had really believed it, he would have had it tried in an ecclesiastical court

Richard couldn’t have truly believed the pre-contract story. If he had, why on earth did he not pass it on to an ecclesiastical court who would have investigated the matter? They were the only ones that had the power to do so.

He certainly had the illegitimacy of the marriage proclaimed in Parliament; but Parliament had no jurisdiction on such matters. Some have claimed that the universal support Richard received from the council is evidence that the tale was believed. But, through the execution of Hastings (and later of Vaughn, Grey and Rivers) without trial, Richard had made it clear to everyone exactly what happened when people opposed him.

4. If it were true, Edward IV would obviously have known about it. Wouldn’t he have taken greater steps to protect his heirs from those ‘in the know’?

The continental writer, Philippe de Commines, claimed that Edward IV’s pre-contract to Talbot was witnessed by Bishop Stillington. The prelate supplied the information to Richard and had previously made it known to George, Duke of Clarence, the ill-fated brother of the two Yorkist Kings.

Supporters of this theory point to a possible association between Stillington and Clarence. They highlight the fact that the Bishop spent a few weeks in prison around the time of Clarence’s execution. But would the ruthless Edward IV really have killed his own brother but let Stillington, the man with the supposed knowledge to destroy his dynasty, off with a warning? Suggestive as the string of circumstances might be, it simply doesn’t stack up.

*

Richard and his supporters believed he should be King. Perhaps some of his reasons were noble. In reality, I suspect it was just the best reaction they could make to the fast-moving events of 1483. Once they had decided that Richard’s kingship was the best possible outcome, a legal pre-text had to be found.

Discrediting Edward IV’s legitimacy was tried. Critiquing the – perfectly legal – way the Wydeville wedding took place was attempted. But ultimately neither could be substantiated.

The pre-contract story had a hint of credibility. Edward IV’s licentiousness was well known. With all the parties dead, it could never be disproved. In other words, the shoe seemed to fit.

It was a cunning and shrewd invention. But it simply doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. As the validity of the pre-contract story crumbles around us, we have no option but to conclude that Richard seized the throne illegally.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

A very brace post, that’ll have the Ricardoians frothing at the mouth, but I think you have a lot of merit on your side. What you have missed is that for any pre-marriage contract for people of this standing to be binding, then the dowry or bride price had to be paid, and the written contract formally witnessed there’s no evidence of either of the latter. So, even if there was an agreement, it’s an invalid contract as not all obligations were fulfilled. Marriage practices in the medieval; period are not as straightforward as they appear. Also, in terms of the “throw it at the wall and see what sticks” approach is also evident in the reference to the Jacquetta witch accusations in the Titulus Regius. What we see in Richard, who was trained to go into the church, is the weaponising of the law to support his claim. What he seems to have overlooked is that by attacking the right of someone to nominate their heir in their last will and testament, he was attacking the inheritance powers of the great families of England. No wonder not everyone backed him when push came to shove.

Thanks for your comments – and your useful additions.

Why was it not mentioned earlier?-Because those in the know were few, and one at least, Edward IV, didn’t intend to allow it to be known. Had Eleanor Talbot, if she wished, challenged the Woodville marriage, alleging her own precontract with Edward, she almost certainly wouldn’t have been able to prove her case. She would have wound up looking at best delusional, at worst deceptive.

There is no evidence, or even indication, that Edward IV’s illegitimacy was presented as an argument before the precontract was raised. In fact, The Crowland Chronicler doesn’t mention it at all. It seems much likelier that Richard only raised the precontract [and witchcraft]; and that the old rumor of Edward’s illegitimacy simply came up in the gossip and talk after Shaa’s sermon.

Ecclesiastical trial? With the throne at stake? Delays, intimidation, bribery, national disruption. Not wise.

Why wouldn’t Edward IV have taken steps to silence Stillington? Perhaps because he thought that Stillington could be trusted to be silent. It was Edward’s alleged illegitimacy that Clarence raised. No detailed accusation of the Woodville marriage’s unlawfulness was asserted by Clarence. So, Edward probably figured that Stillington would be silent. And, remember, Edward died a bit unexpectedly-even to himself.

Thanks for your comments.

There’s no real evidence the story emerged earlier than 1483. It’s possible, of course, but I think we would have a record of it. Gossip would have reached foreign courts.

Had Eleanor challenged it in 1464, she would have found robust support from some powerful people – the likes of Warwick etc.

I suppose people will debate whether Shaa’s sermon was made inspired by Richard’s supporters.

Thanks again

But without a witness, or some writing, Eleanor had no case to present. And if Ms. Troxell’s comment in the public section of this post is correct, that a priest officiating at a secret ceremony might face loss of benefice , or even excommunication, Stillington would have incentive to not support Eleanor.

I’m sorry: I don’t understand your last sentence-as regarded Shaas’ sermon.

But if all this was so, why did the tale ever come to light? If Stillington had a prickle of conscience about the succession, but was worried about the consequences of revealing it, 1469 would have been the time to speak up.

In regard to Sha / Shaw – I suspect that he was speaking on Richard’s instruction. But I recognise that others will think we was acting on his own convictions.

Stillington may simply, in 1483, have considered that he had some obligation to help avoid a Woodville Regency; and it is possible that somehow somebody-Gloucester or another-may have latched on to the secret.

You better believe that Shaa/Shaw was speaking on Richard’s instruction. That doesn’t impeach Shaa’s honesty. He would certainly not have challenged the legitimacy of the young king without some assurance of protection. I’m quite sure he was told what to say; and when to say it.

What does anyone think about.the possibility of Warwick being the inventor of the Precontract story?