“The Princes in the Tower” by Philippa Langley is a book with merits. But with its handling of sources, the work lets itself down and risks betraying a hidden motive. This post explores three examples of how the book uses sources unsatisfactory.

This post is a spin-off from my review/critique of the book. Please read the full review for my take on the positive aspects of the book as well as other criticisms.

Sources, particularly primary sources, are a historian’s building blocks. No, scholar, however accomplished or experienced has authority. Instead, they have authorities: the sources they bring to the table to support their arguments.

To uncover the secrets of the past, simply citing sources is not enough. We must apply due scrutiny and criticism to the evidence in our possession. Philippa Langley’s “Missing Prince’s Project” has done a first-rate job of gathering evidence. But its scrutiny of that evidence is, in my opinion, the biggest flaw in the “Princes in the Tower” book.

Here’s just three examples from the work’s earlier chapters.

1) The Lord Bastard

In Chapter 5, the author draws attention to two payment records. The first is from November 1484. The second, from March 1485. Both reference “the Lord bastard”.

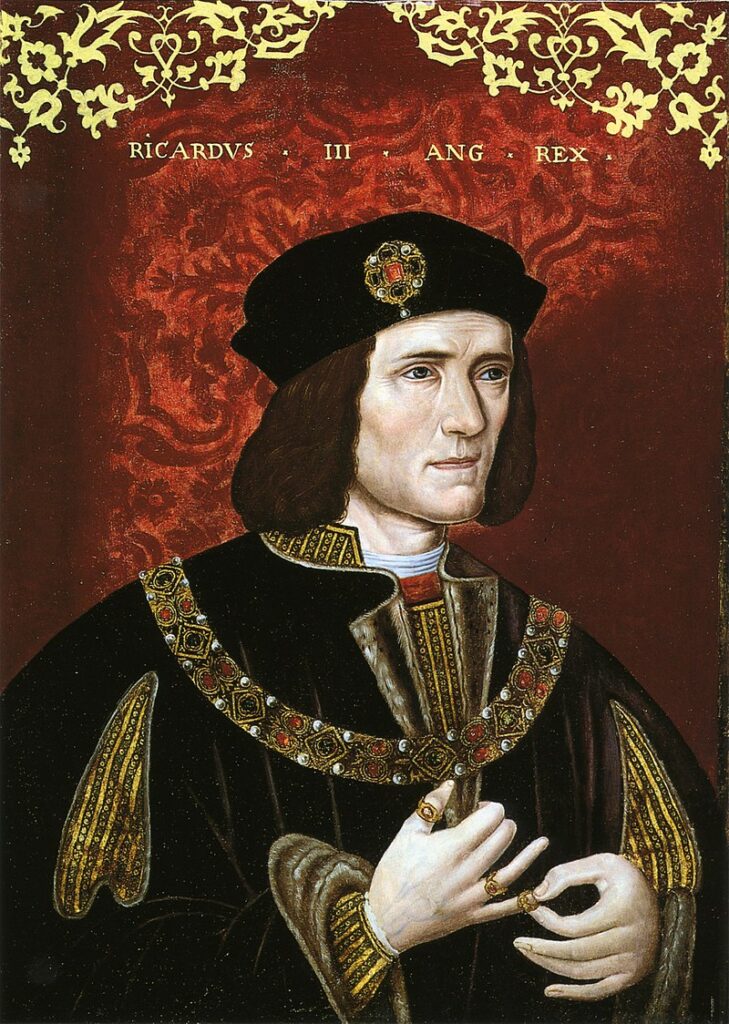

The first, mentions “the Lord Bastard” travelling to Calais. Richard III’s bastard son, John of Gloucester would be made Captain of Calais a few months later. So most historians conclude that the “bastard” in question was Richard’s own, perhaps travelling to the province a few months prior to his official appointment.

The second record acknowledges payments of fine clothes to “the Lord Bastard” and takes place just a couple of days before John was formerly declared Captain of Calais. Such an occasion would warrant him being kitted out in style. It’s this likely that this record too, refers to John.

Langley rejects this view. John, she argues, was not a peer. As such he would not have been named “Lord Bastard”. Instead, she concludes that these records more likely refer to the former Edward V, labelled “Edward the bastard” in other documents. Langley states that though deprived of his throne, the boy was still regarded as Earl of March and Pembroke (possible but improbable), making the title of “Lord” appropriate.

This is an early example of the book’s source criticism falling flat on its face.

We can quickly put paid to the notion that John of Gloucester, as a non-peer, would never have been called “Lord” in administrative records. In 1472, an illegitimate son of Edward IV was described in the household accounts as “my Lord the Bastard”. It’s clearly possible that Richard’s illegitimate son was described likewise.

But even more worryingly, this approach betrays a simplistic understanding of styles of address by assuming that the title of “Lord” was used exclusively for the peerage. Greater familiarity with such records reveals that children of Royals and high-ranking noblemen were often referred to as “Lord” despite having no peerage to speak of. “Lord” and “Lady” were often the chosen forms when referring to someone of high birth who lacked any other accolade.

Such analysis puts too much pressure on the record keepers of the day. They were not heralds. Their job was to record payments and other clerical decisions. The specifics of styles and titles were not their primary concern and it’s typical to find a high degree of title variance among such sources. Royal and noble titles simply weren’t used as consistently in the 1400s as they are today. The child of a King might be referred to as a Prince/Princess or Lord/Lady depending on the author’s preference.

2) The Lille receipt

The biggest single piece of new evidence offered in the book is a receipt for payment issued by a Burgundian administrator to a ‘maker of wooden objects’ in Malines. Dated to December 1487 (the year of the Battle of Stoke) it records payment for 400 long pikes for “lord Martin de Zwarte, a knight from Germany, to take and lead across the sea, Madam the Dowager sent at the time, together with several captains of war from England, to serve her nephew – son of King Edward, late her brother.”

This is clearly a reference to resources for the army, led by Martin Zwarte, that would ultimately combat Henry VII’s forces at Stoke Field. Earlier in 1487, the nobility of Ireland had crowned a Yorkist “King Edward”, which most sources claim was either Edward, Earl of Warwick (son of Edward IV’s brother, the Duke of Clarence) or a pretender posing as him. It was on behalf of this boy that the army marched.

The mention of the son of King Edward, suggests that the writer of the receipt believed that the boy in question was actually one of the “princes in the tower.” Langley takes this as firm evidence that at least one of the Princes survived into 1487. Given that the boy crowned in Ireland (“the Dublin King”) was frequently referred to as “King Edward”, the former Edward V is deemed the most likely candidate.

Earlier in the book, Langley notes that such administrative records are valuable. Unlike the utterings of chroniclers, they are not typically trying to make a political point. They are simply recording facts. As such, they are more likely to be free of bias and agenda.

This is certainly true. But Langley fails to mention the flip side of dealing with such sources: they are recording information for a specific, administrative purpose. They are naturally less interested in any information that is peripheral to that purpose.

In the case of this receipt, the document’s purpose is to record that the wooden pikes have been successfully shipped from A to B and that payment had been rendered. Because of the need to distinguish it from other, potentially similar shipments, such records typically contain enough detail for the context to be clear.

We need to be pragmatic with this kind of information. Were the author and witnesses of this receipts fundamentally concerned about the affairs of England? Was the finer detail of the Yorkist rebellion 1487 of pressing concern to administrators and craftsmen in Burgundy who perhaps viewed the whole affair as a side project of the dowager Duchess? Several paragraphs of the book are spent noting that “high-ranking” officials signed the receipt and would surely not have allowed such an error to pass. Once again, Langley over-estimates the interest of busy officers in such detail. After all, such errors would not have prevented a solitary receipt from serving its purpose.

Nevertheless, the source is interesting. Could it suggest that, at least in some quarters, there was an ambiguity over which Prince or nephew it was that Margaret was championing? But there’s too much to the contrary that the book fails to grapple with. Why, if it was believed in Burgundy that Margaret was championing Edward V, did the rest of Europe – all free from the influence of Henry VII – seem to believe that the boy in question was claiming to be the son of the Duke of Clarence? And, even if it does offer evidence that Margaret claimed or believed the boy to be Edward V, should we really just take it as read that she was correct or telling the truth? Given Margaret’s obvious bias in this situation such a claim should surely be subject to scrutiny.

That this reference to the “son of Edward IV” represents a simple misunderstanding by an administrator not much interested in the affairs of England, is at least as likely an explanation as any other. I also concede that it’s possible that there was some ambiguity around who Margaret was claiming to support. But this source most certainly does not “confirm that at least one of the sons of Edward IV was alive in 1487” as the book so boldly claims.

3) Bernard André

In a bid to bolster the claim that Edward V was “the Dublin King” that faced Henry VII at the Battle of Stoke, the book draws attention to an argument from Matthew Lewis. Bernard André, court poet and biographer of Henry VII notes in his account that the pretender in Ireland in 1487 was claiming to be “the son of Edward the Fourth”. Recognising that Edward V would attract more support than his cousin Warwick, the government must have twisted the story. But in a moment of madness, André let the truth slip into his work.

What this book fails to mention, however, (though Lewis does) is that Andre’s confused account claims the boy to be Richard, the younger son rather than Edward, the elder. This dilutes its usefulness as evidence of Edward V’s survival.

There are at least two possible explanations as to this mention of Edward IV’s son in Andre’s account:

- Langley and Lewis are correct, and André believed that a son of Edward IV, or someone posing as one, was lurking in Ireland. But for this to be the case, the theorists are asking a lot of André. All at the same time, he has to have been trusted enough to be told the “real” story of the Battle of Stoke, but sufficiently unreliable to later forget that it was a state secret. It requires the poet to have been sharp enough to remember that a son of Edward IV was on the scene, but scatty enough to forget which son it was.

- André was confusing the events of 1487 with the later campaign by Perkin Warbeck/Richard, Duke of York. After all, both campaigns began in Ireland. And in the 1490s, it certainly was the name of the younger son of Edward IV that was being bandied about.

Bernard André had served as a tutor to Arthur, Prince of Wales, Henry VII’s eldest son. When I was writing my biography of Arthur, I naturally spent a lot of time with Andre’s works. It’s important that we understand what kind of source we’re dealing with.

What survives of the poet’s biography of Henry VII (which is the source in question) is highly disorganised and clearly a draft in its early stages. He was a blind man dictating to a scribe. Frequently throughout the document, he leaves blank spaces where he can’t remember the detail, making a plan to check information and return to it later.

If André had finished his account, perhaps it would serve as a useful source. Sadly, while fascinating and bursting with potential, the version we have can rarely be relied upon. With all this in mind, isn’t it more likely that his reference to a son of Edward IV represents a confusion of the mind rather than a casual betrayal of a closely-guarded secret?

*

To its credit, Langley’s book references a rich range of sources. I am not as familiar with many of them as I am with André’s work or late medieval/early Tudor record keeping. But having seen the unsatisfactory treatment of the sources that I do know well, I find it difficult to put my faith in her handling of the remainder.

If this book is designed to do little more than put fuel in the fire of those who already believe in Richard III’s innocence, then it will serve its purpose. What’s such a shame, is that it has the potential to make a meaningful contribution to the scholarly debate. But with such partisan source criticism serving as a characteristic of the book, such an opportunity will quickly evaporate.