John, duke of Somerset was a ‘Lancastrian prince’ who married beneath him. Was this an act of passion or were more pragmatic considerations in mind?

I’m going to let you into a little secret. At heart I’m a romantic. I think most Royal History Geeks are.

When I’m delving into the tales of England’s history, the personal lives and misadventures of those who shaped it always spark my curiosity. I’m as interested in them as I am the political, military or dynastic significance of their actions.

So as you can imagine, my sense of intrigue goes into overdrive when I think I’ve discovered that rare thing: a genuine medieval love match.

For a time I thought I had found just that in the union of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset and Margaret Beauchamp. Could it be that the parents of Margaret Beaufort and grandparents of Henry VII had married for love?

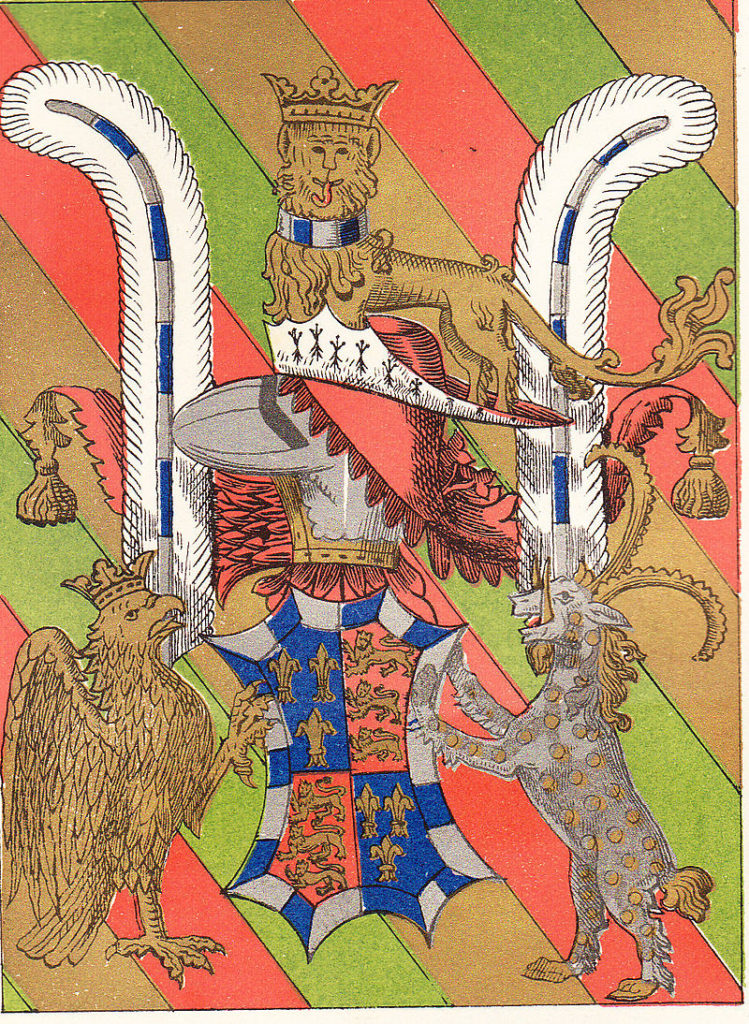

Let’s review the facts. John Beaufort moved in the upper reaches of nobility. He considered himself a Lancastrian prince. His status was high and he was in search of a fortune to match. The Earl of Somerset (as he then was) wanted to enter the league of the great landowners of the realm like York and Buckingham. And he also had a staggering ransom to pay off.

Margaret Beauchamp was no slouch. She was from the top tier of the gentry and a landowner in her own right. But she was no aristocrat or major heiress. Besides, she already had children from a previous marriage. While her lands were not insignificant, they were unlikely to be inherited by a Beaufort descendant.

If money could not be the reason for their match, could the motivation have been more tender?

As I further explored the story of the pair, the tale of love seemed to continue. Ahead of setting off to war, John negotiated that should he die, his wife would retain the wardship of their then-unborn child. He was ensuring that mother and child would not be separated. Surely that can only be interpreted as an act of affection?

It was a wonderful thought. Sadly, it was one not informed by the realities of the time.

To a true Royal History Geek, there’s no such thing as too much research. Every facet of context we can absorb illuminates another piece of the picture we are trying to build. But I would have to concede that when you delve deeper and deeper into the economic and political structures of the day, you must prepare for romantic notions to be shattered.

John and Margaret are a case in point.

Elizabeth Norton was the first writer to set me straight on John and Margaret’s union. Margaret may not have been the sort of wife that a man of Somerset’s stature had dreamt of. But she was probably the best catch available. Having been imprisoned in France for 20 years, most of the prized brides of his generation had already been snapped up. Margaret, with her modest inheritance, could at least contribute something financially while he tightened his belt to pay off his ransom.

But what about Somerset’s negotiation with the King that his wife should keep their child’s wardship? Surely that could still be significant.

Significant it certainly was. But it’s probably not wise to interpreted it as an act of love.

Instead it should be understood as an attempt by the (by then) Duke of Somerset to protect the inheritance of his heir.

Had Somerset died while his child was a minor it would have created a ‘feudal incident’. And these were what 14th century landowners feared above all else.

As Somerset held land directly from the King, Henry VI would have assumed responsibility for the young child. He would have granted his or her ‘wardship’ to someone currently in his favour. For the duration of the child’s minority, their ‘guardian’ would have taken responsibility for the Beaufort lands – and received all associated revenues. Crucially, whoever held the child’s wardship would control their marriage. He could literally sell it to the highest bidder.

The child’s guardian could not deprive the heir permanently of their lands. But they could manage the estate in a way that would maximise short term revenue at the expense of responsible stewardship.

They could also try and ‘asset strip’ the estate by granting facets of land out to trust. This might prevent the heir from coming into the fullness of their revenue when they came of age. Such measures could be challenged legally. But it represented a clear risk to the child’s long-term best interests.

In the possible event of his early death, who could Somerset really trust to act in the best interest of his heir? Even his younger brother would have looked jealously upon the Beaufort lands that the offspring had inherited. Quite simply, only his duchess would possess a real interest in careful stewardship of the Somerset estate. Only Margaret could have been trusted to negotiate the best possible marriage for their child. And it is for these more economic and dynastic reasons, that the Duke would have been so keen to ensure that wardship fell to her.

Of course, none of this is evidence that the pair weren’t a love match. It could be argued that attempting to secure the wardship for his wife was still an act of consideration, if not affection. It could also be read as a mark of respect. Unlike most women of the day, Margaret had experience as a landowner. She had demonstrated the competence to look after her child’s affairs.

A romantic streak is an asset to anyone exploring the stories of our forebears. It sparks our interest and encourages us to dig a little deeper. However, if our first commitment is to the facts of history, we must always be prepared to revise our romance when our understanding of the era deepens.