Favouritism could be the downfall of a medieval king. But a measured and sustained favouring of the Beauforts by their Lancastrian kin drew the family into the centre of England’s nobility.

When Edward IV usurped the throne in 1461, he made both his brothers dukes. Huge landed estates were bestowed on each of them. As they grew up, he drew them deeper into the governance of the realm.

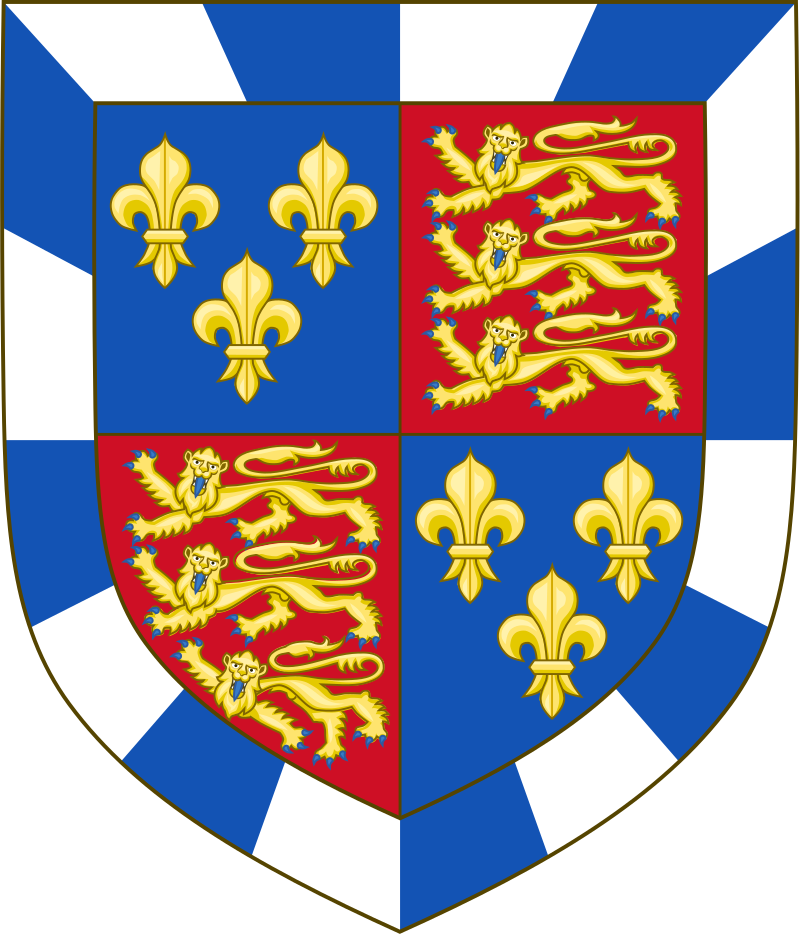

At first, glance, this contrasts sharply with the actions of that other famous usurper, Henry IV. When he seized the throne in 1399 his brother, John Beaufort was reduced in rank from Marquess of Dorset to Earl of Somerset. At no single point was a major land endowment offered. The king even went out of his way to proclaim that descendants of his Beaufort kin could never be contenders for the crown.

Was it something they said?

But these isolated instances distort the truth. Under the house of Lancaster, the Beauforts reached the summit of society.

As Royal History Geeks will know, the Beaufort family finds its origins in the birth of John in 1374. The illegitimate son of John of Gaunt and his mistress, Katherine Swynford was soon joined by three siblings.

As children of the richest man in England and grandchildren of Edward III, the lives of the first Beauforts were never going to be ordinary. But as bastards, their prospects were unlikely to be great. Their parents eventually married and the Beauforts’ were legitimisation in the 1390s. But few could have predicted how the dynasty would become interwoven with the politics of the following century.

The advancement of the Beauforts has its roots in the reign of Richard II. But it reached a new level when their half-brother usurped the throne as Henry IV.

The best example of how advanced the Beauforts were by their Lancastrian kin is their rapid acquisition of land. By the end of the 1440s they were the dominant landowners in Somerset and a major landed player in the Westcountry. Just 50 years before, they didn’t own a single square meter in the county.

It isn’t just the speed and volume of land acquisition that’s significant. It’s the location. In the late medieval period, landowners were desperate to consolidate their landholdings in an individual country. It cemented their Lordship. But kings were determined to frustrate such ambitions. The idea of nobles building unwieldy regional power bases did not appeal. When large estates were granted, they were typically regionally disparate.

In consolidating their power in Somerset, the medieval historian Chris Given-Wilson notes that the Beauforts enjoyed their share of luck. But such a speedy consolidation would not have been possible without royal support. The Lancastrian Kings had significantly bent the rules for the advancement of the Beaufort relatives. As a mark of high favour, this cannot be underestimated.

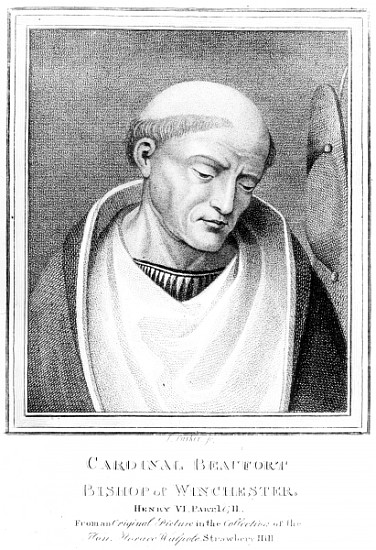

From the earliest days of Henry IV’s reign, it was clear that the Beauforts were a family in favour. John was constantly in his brother’s company. He held high and lucrative offices such as the Captaincy of Calais. Henry Beaufort served as Lord Chancellor. Joan remained a countess though many had expected her husband to be reduced in rank. The young Thomas was set on a path of advancement that would one day see him become Duke of Exeter.

But why, if the family were in favour, did it take three generations for their advancement to truly be cemented. The answer lies in the very real constraints that bound medieval kingship – or at least should if a king were to be successful.

It’s tempting to think of medieval kings as absolute despots with the power to dispense patronage as they see fit. History, however, had taught all kings to be cautious. All, that is, but the most foolish.

Extreme favouritism made a king vulnerable. When a lesser man was plucked out of nowhere and rapidly raised above the nobility of the day, the political order was in danger of collapse.

This was not simply because such actions ruffled the feathers of proud aristocrats. It was because extreme favouritism undermined the whole system of lordship on which the government in medieval England was predicated.

A lord built his power base on the land he held and the ‘affinity’ he was able to build in the shires and counties in which he was a major landholder. If land was given to an unworthy favourite, there was less for the established nobility.

But the problem went deeper than that.

A lord’s affinity in counties and shires where they were dominant (their ‘countries’ as they called them) depended on an unwritten, but very real code. If the gentry and players of that community would honour the lordship of the major landowner, that Lord would, in turn, act in their favour. It was never as crude as a quid-pro-quo. But through his access to the King, a lord could obtain justice, maintain order and open up possibilities for advancement.

For all of this, a lord needed the ear of the king. And to be perceived as having the ear of the king.

This was a reasonable expectation. The nobility was the ordained body with whom the King should socialise, fraternise and consult. But in a time when favourites had come to prominence, the natural order of things was distorted. If a King was beholden to the advice of his favourites – government by clique – what confidence could people have that the nobility were listened to? A Lord was at risk of losing his affinity. Collectively, this is something the nobility were unlikely to suffer for long.

All Kings were mindful of this. And none more so than Henry IV. He had had just overthrown a King renowned for favouritism. He was likely to be extra sensitive to it.

None of this means King’s didn’t have favourites. Edward IV had William Hastings. Henry VII advanced his stepfather. But for favouritism to be tolerated, it had to be measured, moderate and gradual. This was the policy that Henry IV would pursue with his Beaufort kin.

I began this post by contrasting the Beauforts with the siblings of Edward IV. But really that’s like comparing apples and oranges. The house of York claimed to be the senior descendants of Edward III. The late duke of York had been recognised as rightful king of England. Edward IV’s brothers were treated as sons of a king. A dukedom was their birth right.

In 1399, however, Henry IV had (rather spuriously) claimed the throne through his mother. The status of his paternal half-siblings remained unaffected.

Besides, the Beauforts never really lost the taint of bastardy. Once they were legitimised the nobility welcomed them to their ranks. But they were never really accepted as royalty.

Good kings acted within the constraints of certain expectations. For a usurper like Henry IV to survive, patronage had to be used sparingly and strategically. That measured and sustained favouritism was focused on the Beauforts. In the dark days of the Wars of the Roses, that constant favour would be repaid in full.

Subscribe to our newsletter!