I’ve never been that interested in the debate around ‘when medieval England ended.’ It’s not a question that a contemporary could ever have asked and I don’t totally see the point in it.

Nonetheless I agree that saying the battle of Bosworth field was the ‘end of the medieval era’ is far too simplistic. People would not have looked out of their windows the day after and seen a radically different world.

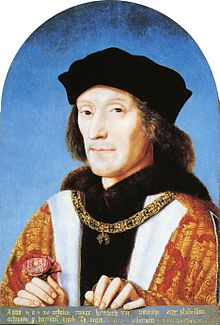

That said, it is clear that the Tudor dynasty ushered in a new era in the way that England was governed. What fascinates me at the moment, is how much that may have been down (at least in part) to Henry VII’s personal style of Kingship.

I like Henry. It’s a shame that he gets so little attention in comparison to his showy son and chaotic Yorkist predecessors. But I genuinely believe he was a man of good character. Part of the reason for this, is that I believe he was less blood thirsty than your typical ruler – even if he was not adverse to tyrannical tendencies.

On the fact of it, my claim seems strange. This is, after all, a man who won the crown in battle and had to bear arms more than once to defend it. But when we take a minute to consider the context and other facts, I do think my comments have some credibility. For example:

- He did not seek glory in foreign battles. Establishing his claim to the French throne was of little interest to him in contrast to the Henrys that had gone before him and the one that would succeed him. There is an added irony to this in that he was the grandson of a French princess and arguably had a far greater claim to that throne than he did to the one he occupied.

- He was remarkably lenient with those who crossed him, Perkin Warbeck being the most obvious example. This is not to say that he wasn’t a man of his times. His eventual murder (because that’s what it was) of the vulnerable Earl of Warwick was almost unforgivable – but it seems that he did this for the sake of his dynasty rather than out of any blood lust.

- He did not generally take part in battles himself. You could argue this made him a coward. But it does reinforce the argument that tales of great chivalry and conquest were of little personal interest to him.

Perhaps, after the Wars of the Roses, he thought England bored of battle. Maybe his own experience of a life on the run had exhausted his appetite for conquest. But whatever else can be said in critique of the miserly usurper, Henry Tudor, I would much rather live in a country with a high tax economy than one where my life was often in danger.